This page is for printing out the case studies on the subject of Web/access. Note that some of the internal links may not work.

e-MapScholar, a JISC 5/99 funded project, aims to develop tools and learning and teaching materials to enhance and support the use of geo-spatial data currently available within tertiary education in learning and teaching, including digital map data available from the EDINA Digimap service. The project is developing:

The Disability Discrimination Act (1995) (DDA) aimed to end discrimination faced by many disabled people. While the DDA focused mainly on the employment and access to goods and services, the Special Education Needs and Disability Act (2001) (SENDA) amended the DDA to include education. The learning and teaching components of SENDA came into force in September 2002. SENDA has repercussions for all projects producing online learning and teaching materials for use in UK education because creating accessible materials is now a requirement of the JISC rather than a desirable project deliverable.

This case study describes how the e-MapScholar team has addressed accessibility in creating the user interfaces for the learning resource centre, case studies, content management system and virtual placement.

Figure 1: Screenshot of the case study index |

Figure 2: Screenshot of the learning resource centre resource selection page |

Figure 3: Screenshot of the content management system |

Figure 4: Screenshot of the Virtual Placement (temporary - still under development) |

An accessible Web site is a Web site that has been designed so that virtually everyone can navigate and understand the site. A Web site should be informative, easy to navigate, easy to access, quick to download and written in a valid hypertext mark up language. Designing accessible Web sites benefits all users, not just disabled users.

Under SENDA the e-MapScholar team must ensure that the project deliverables are accessible to users with disabilities including mobility, visual or audio impairments or cognitive/learning issues. These users may need to use specialist browsers (such as speech browsers) or configure their browser to enhance the usability of Web sites (e.g. change font sizes). It is also a requirement of the JISC funding that the 5/99 projects should reach at least priority 1 and 2 of the Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) standards and where appropriate, priority 3.

The project has been split into four major phases:

While the CMS and learning units are inter-connected, the other components can exist separately from one another.

The project has employed a simple and consistent design in order to promote coherence and also to ease navigation of the site. Each part employs similar headings, navigation and design.

The basic Web design was developed within the context of the learning units and was then adapted for the case studies and virtual placement.

Summaries, learning objectives and pre-requisites are provided where necessary.

Links to help page are provided. The help page will eventually provide information on navigation, how to use the interactive tools and FAQ in the case of learning units and details of any plug-ins/software used in the case studies.

Font size will be set to be resizable in all browsers.

Verdana font has been used as this is considered the most legible font face.

CSS (Cascading style sheets) have been used to control the formatting of text; this cuts out the use of non-functional elements, which could interfere with text reader software.

Navigation has been used in a consistent manner.

All navigational links are in standard blue text.

All navigation links are text links apart from the learning unit progress bar, which is made up of clickable images. These images include an ALT tag describing the text alternative.

The progress bar provides a non-linear pathway through the learning units, as well as providing the user with an indication of their progress through the unit.

The link text used can be easily understood when out of context, e.g. "Back to Resource" rather than "click here".

'Prev' and 'Next' text links provide a simple linear pathway through both the learning units and the case studies.

All links are keyboard accessible for non-mouse users and can be reached by using the tab key.

Where possible the user is offered a choice of pathway through the materials e.g. the learning units can be viewed as a long scrolling page or page-by-page chunks.

Web safe colours have been used in the student interface.

The interface uses a white background ensuring maximum contrast between the black text, and blue navigational links.

Very few graphics have been used in the interface design to minimise download time.

Content graphics and the project logo have ALT tags providing a textual description.

Long descriptions will be incorporated where necessary.

Graphics for layout will contain "" (i.e. null) ALT tags so they will be ignored by text reader software.

Tables have been used for layout purposes complying with W3C standards; not using structural mark-up for visual formatting.

HTML 4.0 standards have been complied with.

JavaScript has been used for the pop-up help menu, complying with JavaScript 1.2 standards.

The user is explicitly informed that a new window is to be opened.

The new window is set to be smaller so that it is easily recognised as a new page.

Layout is compatible with early version 4 browsers, both in Netscape, Internet Explorer and Opera.

Specific software or plug-ins are required to view some of the case study materials e.g. GIS or AutoCAD software has been used in some of the case studies. Users will be advised of these and where possible will be guided to free viewers. Where possible the material will be provided in an alternative format such as screen shots, which can be saved as an image file.

Users are warned when non-HTML documents (e.g. PDF or MS Word) are included in the case studies and where possible documents are also provided in HTML format.

Problems experienced have generally been minor.

Throughout the project accessibility has been thought of as an integral part of the project and this approach has generally worked well. Use of templates and CSS have helped in minimising workload when a problem has been noted and the materials updated.

It is important that time and thought goes into the planning stage of the project as it is easier and less time consuming to adopt accessible Web design in an early stage of the project than it is to retrospectively adapt features to make them accessible.

User feedback from evaluations, user workshops and demonstrations has been extremely useful in identifying potential problems.

Deborah Kent

EDINA National Data Centre

St Helens Office

ICT Centre

St Helens College

Water St

ST HELENS

WA10 1PZ

Email: dkent@ed.ac.uk

Lynne Robertson

Geography

School of Earth, Environmental and Geographical Sciences

The University of Edinburgh

Drummond Street

Edinburgh EH8 9XP

Email: lr@geo.ed.ac.uk

Figure 1: The Library Online Entry Point

Library Online [1] (shown in Figure 1) is the main library Web site/portal for the University of Edinburgh [2]. Although clearly not a project site in itself, one of its functions is to provide a gateway to project sites with which the Library is associated [3].

In the last seven years or so it has grown to around 2,000 static pages plus an increasing amount of dynamic content, the main database-driven service being the related web-based Library Catalogue [4]. At the time of writing (October 2003), a proprietary Digital Object Management System has been purchased and is being actively developed. This will no doubt impinge on some areas of the main site and, in time, probably the Catalogue: notably access to e-journals and other digital resources/collections. However, for the time being, Library Online and the Catalogue between them provide the basic information infrastructure.

The challenges include enhancing accessibility and usability; also maintaining standards as these develop. Problems exist with legacy (HTML) code, with increasingly deprecated layout designs and separating content from presentation. Addressing these issues globally presents real problems whilst maintaining currency and a continuous, uninterrupted service. It is, of course, a live site - and an increasingly busy one. There are currently over twenty members of staff editing and publishing with varying levels of expertise and no overall Content Management System, as such.

Policy has also been to maintain support for a whole range of older browsers, further complicating matters.

Fortunately, the site design was based on Server-Side Includes (SSIs) and a great deal of effort was put into conforming to best practice guidelines as they were articulated over five years ago. The architecture appears to remain reasonably sound. So an incremental approach has been adopted generally, though some enhancements have been achieved quite rapidly across the board by editing sitewide SSIs. A recent example of the latter has been the introduction of the "Skip Navigation" accessibility feature across the whole site.

A fairly radical redesign of the front page was carried out within the last two years. This will need to be revisited before too long but the main focus is presently on the body of the site, initially higher level directories, concentrating on the most heavily-used key areas.

Enhancements to accessibility and usability are documented in our fairly regularly updated accessibility statement [5]. These include:

None of these features should be contentious, though precise interpretations may vary. Many have been built in to the design since day one (e.g. "alt" tags); others have been applied retrospectively and incrementally. All are, we hope, worthwhile!

Additional functionality with which we are currently experimenting includes media styles, initially for print. The original site navigation design was quite graphically rich and not very "printer-friendly". Progress is being made in this area - but who knows what devices we may need to support in the future? Perhaps we shall eventually have to move to XML/XSLT as used within our Collections Gateway due for launch soon. Meanwhile, for Library Online, even XHTML remains no more than a possibility at present.

Our approach to site development is essentially based on template and stylesheet design, supported by Server-Side Include technology for ease of management and implementation. This largely takes care of quality assurance and our proposed approach to content management should underpin this. We are moving towards fuller adoption of Dreamweaver (MX) for development and Macromedia Contribute for general publishing. Accessibility and usability quality assurance tools are already in regular use including LIFT Online and other resources identified on the site. It seems very likely that this will continue.

All this remains very much work in progress ... Upgrading legacy code, layout design, integration and interoperability with other information systems etc. Categorically, no claims are made for best practice; more a case of constantly striving towards this.

The main problems experienced - apart from time and resources naturally - have been:

With the benefit of hindsight, perhaps stylesheets could have been implemented more structurally. Validity has always been regarded as paramount, while separation of true content from pure presentation might have been given equal weight(?) This is now being reassessed.

We might have derived some benefit from more extensive database deployment - and may well in the future - but we must constantly review, reappraise possibilities offered by new technologies etc. and, above all, listen to our users.

I have referred to some significant developments in prospect which present more opportunities to do things differently - but whether we get these right or wrong, there will always be scope for improvement on the Web, just as in the "real" world. Like politics, it seems to be the art of the possible - or should that be a science?

Steve Scott, Library Online Editor (steve.scott@ed.ac.uk)

For QA Focus use.

The NMAP project [1] was funded under the JISC 05/99 call for proposals to create the UK's gateway to high quality Internet resources for nurses, midwives and the allied health professions.

NMAP is part of the BIOME Service, the health and life science component of the national Resource Discovery Network (RDN), and closely integrated with the existing OMNI gateway. Internet resources relevant to the NMAP target audiences are identified and evaluated using the BIOME Evaluation Guidelines. If resources meet the criteria they are described and indexed and included in the database.

NMAP is a partnership led by the University of Nottingham with the University of Sheffield and Royal College of Nursing (RCN). Participation has also been encouraged from several professional bodies representing practitioners in these areas. The NMAP team have also been closely involved with the professional portals of the National electronic Library for Health (NeLH).

The NMAP service went live in April 2001 with 500 records. The service was actively promoted in various journal, newsletters, etc. and presentations or demonstrations were given at various conference and meetings. Extensive use was made of electronic communication, including mailing lists and newsgroups for promotion.

Work in the second year of the project included the creation of two VTS tutorials: the Internet for Nursing, Midwifery and Health Visiting, and the Internet for Allied Health.

As one of the indicators of the success, or otherwise, in reaching the target group we wanted to know how often the NMAP service was being used, and ideally who they are and how they are using it.

The idea was to attempt to ensure we were meeting their needs, and also gain data which would help us to obtain further funding for the continuation of the service after the end of project funding.

There seems to be little standardisation of the ways in which this sort of data is collected or reported, and although we could monitor our own Web server, the use of caching and proxy servers makes it very difficult to analyse how many times the information contained within NMAP is being used or where the users are coming from.

These difficulties in the collection and reporting of usage data have been recognised elsewhere, particularly by publishers of electronic journals who may be charging for access. An international group has now been set up to consider these issues under the title of project COUNTER [2] which has issued a "Code of Practice" on Web usage statistics. In addition QA Focus has published a briefing document on this subject [3].

We took a variety of approaches to try to collect some meaningful data. The first and most obvious of these is log files from the server which were produced monthly and gave a mass of data including:

A small section of one of the log files showing the general summary for November 2002 can be seen below. Note that figures in parentheses refer to the 7-day period ending 30-Nov-2002 23:59.

Successful requests: 162,910 (39,771) Average successful requests per day: 5,430 (5,681) Successful requests for pages: 162,222 (39,619) Average successful requests for pages per day: 5,407 (5,659) Failed requests: 2,042 (402) Redirected requests: 16,514 (3,679) Distinct files requested: 3,395 (3,217) Unwanted logfile entries: 51,131 Data transferred: 6.786 Gbytes (1.727 Gbytes) Average data transferred per day: 231.653 Mbytes (252.701 Mbytes)

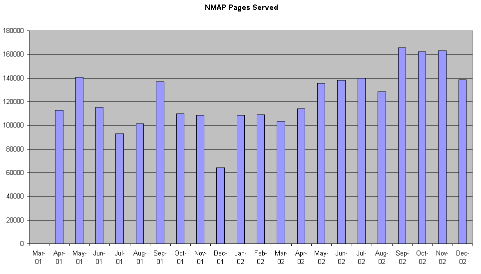

A graph of the pages served can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Pages served per month

The log files also provided some interesting data on the geographical locations and services used by those accessing the NMAP service.

Listing domains, sorted by the amount of traffic, example from December 2002, showing those over 1%.

| Requests | % bytes | Domain |

| 48237 | 31.59% | .com (Commercial) |

| 40533 | 28.49% | [unresolved numerical addresses] |

| 32325 | 24.75% | .uk (United Kingdom) |

| 14360 | 8.52% | ac.uk |

| 8670 | 7.29% | nhs.uk |

| 8811 | 7.76% | .net (Network) |

| 1511 | 1.15% | .edu (USA Educational) |

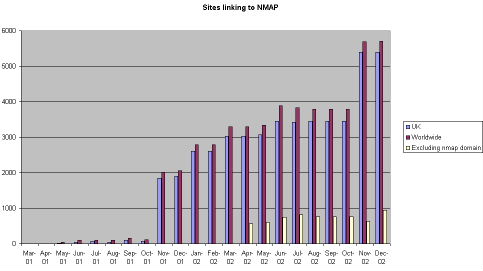

A second approach was to see how many other sites were linking to the NMAP front page URL. AltaVista was used as it probably had the largest collection back in 2000 although this has now been overtaken by Google. A search was conducted each month using the syntax: link:http://nmap.ac.uk and the results can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2 - Number of sites linking to NMAP (according to AltaVista)

The free version of the service provided by InternetSeer [4] was also used. This service checks a URL every hour and will send an email to one or more email addresses saying if the site is unavailable. This service also provides a weekly summary by email which, along with the advertising includes a report in the format:

========================================

Weekly Summary Report

========================================

http://nmap.ac.uk

Total Outages: 0.00

Total time on error: 00:00

Percent Uptime: 100.0

Average Connect time*: 0.13

Outages- the number of times we were unable to access this URL

Time on Error- the total time this URL was not available (hr:min)

% Uptime- the percentage this URL was available for the day

Connect Time- the average time in seconds to connect to this URL

During the second year of the project we also conducted an online questionnaire with 671 users providing data about themselves, why they used NMAP and their thoughts on its usefulness or otherwise, however this is beyond the scope of this case study and is being reported elsewhere.

Although these techniques provided some useful trend data about the usage of the NMAP service there are a series of inaccuracies, partly due to the nature of the Internet, and some of the tools used.

The server log files are produced monthly (a couple of days in areas) and initially included requests from the robots used by search engines, these were later removed from the figures. The resolution of the domains was also a problem with 28% listed as "unresolved numerical addresses" which gives no indication where the users is accessing from. In addition it is not possible to tell whether .net or .com users are in the UK or elsewhere. The number of accesses from .uk domains was encouraging and specifically those from .ac & .nhs domains. It is also likely (from data gathered in our user questionnaire) that many of the .net or .com users are students or staff in higher or further education or NHS staff who accessing the NMAP service via a commercial ISP from home.

In addition during the first part of 2002 we wrote two tutorials for the RDN Virtual Training Suite (VTS) [5], which were hosted on the BIOME server and showed up in the number of accesses. These were moved in the later part of 2002 to the server at ILRT in Bristol and therefore no longer appear in the log files. It has not yet been possible to get access figures for the tutorials.

The "caching" of pages by ISPs and within .ac.uk and .nhs.uk servers does mean faster access for users but probably means that the number of users in undercounted in the log files.

The use of AltaVista "reverse lookup" to find out who was linking to the NMAP domain was also problematic. This database is infrequently updated which accounts from the jumps seen in Figure 2. Initially when we saw a large increase in November 2001 we thought this was due to our publicity activity and later realised that this was because it included internal links within the NMAP domain in this figure, therefore from April 2002 we collected another figure which excluded internal links linking to self.

None of these techniques can measure the number of times the records from within NMAP are being used at the BIOME or RDN levels of JISC services. In addition we have not been able to get regular data on the number of searches from within the NeLH professional portals which include an RDNi search box [6] to NMAP.

In the light of our experience with the NMAP project we recommend that there is a clear strategy to attempt to measure usage and gain some sort of profile of users of any similar service.

I would definitely use Google rather than AltaVista and would try to specify what is needed from log files at the outset. Other services have used user registration and therefore profiles and cookies to track usage patterns and all of these are worthy of consideration.

Rod Ward

Rod Ward

Lecturer, School of Nursing and Midwifery,

University of Sheffield

Winter St.

Sheffield

S3 7ND

Email: Rod.Ward@sheffield.ac.uk

Also via the BIOME Office:

Greenfield Medical Library

Queen's Medical Centre,

Nottingham NG7 2UH

Email: rw@biome.ac.uk

Gathering Usage Statistics and Performance Indicators: The NMAP Experience,

Ward, R., QA Focus case study 06, UKOLN,

<http://www.ukoln.ac.uk/qa-focus/documents/case-studies/case-study-06/>

This document was published on 8th January 2003.

MIMAS [1] is a JISC-funded service [2] which provides the UK higher education, further education and research community with networked access to key data and information resources to support teaching, learning and research across a wide range of disciplines. Services supported by MIMAS include the ISI Web of Science Service for UK Education, CrossFire, UK Census aggregate statistics, COPAC, the Archives Hub, JSTOR, a Spatial Data service which includes satellite data, and a new International Data Service (part of the Economic and Social Data Service) [3].

This document describes the approaches which have been taken by MIMAS to ensure that its services provide levels of accessibility which are compatible with MIMAS's available resources and the services it provides.

The work was carried out in order to ensure that MIMAS services are compliant with the SENDA legislation wherever possible.

A MIMAS Project Management Team called ACE (Accessibility Compliance Exercise) was set up with the remit of making recommendations on accessibility work. We were set the task of making the MIMAS Web site compliant at least with Priority 1 WAI guidelines [4] by 1 September 2002.

The ACE Team consisted of a coordinator and four members of MIMAS staff with a range of skills, and chosen so that each section manager (of which there are three) had at least one person on the team. We knew that it would take a great deal of effort from many members of staff and that it was crucial to have the support of all managers.

The coordinator reported to the MIMAS and Manchester Computing management team and left technical issues to the rest of the team.

The team went about identifying the services, projects, areas of the MIMAS Web sites and other items which are supported and/or hosted by MIMAS.

Usually the creator or maintainer, but in some cases the section manager was identified as the person responsible for each area and a member of the ACE team (the "ACE contact") was assigned to assist and monitor progress.

We drew a distinction between Web pages (information), data and applications. It took some time to get the message through to all staff that ACE (and SENDA) was concerned with all aspects of the services and that we needed to check applications as well as Web pages. We could all have some informed opinion about Web pages, but applications often required an expert in the area to think about the accessibility of a package. Managers were asked to request and gather statements from suppliers on the accessibility of their products.

A Web page was set up on the staff intranet to document the progress each service was making, who the main players were, and to summarise areas of concern that we needed to follow up. This helped the ACE Team to estimate the scope of any work which was needed, and managers to allocate time for staff to train up in HTML and accessibility awareness. We also provide notes on how to get started, templates, training courses etc., and we continue to add information that we think will help staff to make their pages more accessible.

The ACE team met fortnightly to discuss progress. Members of the team recorded progress on the staff intranet, and the coordinator reported to the management team and to others in the Department (Manchester Computing) engaged in similar work.

The ACE team recommended that MIMAS Web resources should aim to comply with at least WAI Priority 1 guidelines. The ACE team had the following aims:

Software (Macromedia's LIFT) was purchased to assist staff evaluate their pages, and extra effort was brought in to assist in reworking some areas accessible.

The ACE team set up an area on the staff intranet. As well as the ongoing progress report, and information about the project and the ACE team this contained hints and tips on how to go about evaluating the accessibility of Web pages, validating the (X)HTML, how to produce an implementation plan, examples of good practice etc.

Other information on the Staff intranet included:

The ACE team had their own pages to make accessible, whilst also being available o help staff who needed guidance with their own Web sites. We all had our usual day jobs to do, and time was short.

Some Web sites needed a lot of work. We brought in external help to rework two large sites and encouraged the systematic use of Dreamweaver in order to maintain the new standards. Using the Dreamweaver templates prepared by the ACE team helped those staff who were not that familiar with HTML coding.

Although Manchester computing and JISC put on Accessibility courses, not all staff were able to attend. Group meetings were used to get the message across, and personal invitations to attend the ACE workshops were successful in engaging HTML experts, managers, programmers and user support staff.

There was still a lot to do after September 2002. Not all sites could reach Priority 1 by September 2002. For these, and all services, we are recommending an accessibility statement which can be reached form the MIMAS home page. We continue to monitor the accessibility of Web pages and are putting effort into making Web sites conform to the local conventions that we have now set out in the MIMAS Accessibility Policy. This Policy is for staff use, rather than a public statement, and is updated from time to time. Accessibility statements [7] are specific to each service.

In January and February 2003, the ACE team ran a couple of workshops to demonstrate key elements of the ACE policy - e.g. how to validate your pages, and to encourage the use of style sheets, Dreamweaver, and to discuss ways of making our Web sites more accessible generally.

We still have to ensure that all new staff are sent on the appropriate Accessibility courses, and that they are aware of the standards we have set and aim to maintain.

Workshops help everyone to be more aware of the issues and benefited the ACE team as well as staff. Because of time constraints we were unable to prepare our won ACE workshops until January 2003, by which time most sites were up to Level 1. Other people's workshops (eg. the JISC workshop) helped those attending to understand the issues relating to their own sites, those maintained by others at MIMAS, and elsewhere.

Talking to staff individually, in small groups, and larger groups, was essential to keep the momentum going.

It would have been helpful to be more specific about the accessibility features we want built in to the Web sites. For example, we encourage "skip to main content" (Priority 3), and the inclusion of Dublin Core metadata.

Anne McCombe

MIMAS

University of Manchester

For QA Focus use.

The Economic and Social Data Service

(ESDS) [1]

is a national data archiving and dissemination service which came into operation

in January 2003.

The Economic and Social Data Service

(ESDS) [1]

is a national data archiving and dissemination service which came into operation

in January 2003.

The ESDS service is a jointly-funded initiative sponsored by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) [2] and the Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC) [3].

Many Web sites fail to comply with accessibility and usability guidelines or consist of valid code. Prior to setting up the ESDS Web site it was decided that a Web Standards Policy would be agreed upon and adhered to.

The ESDS Web Standards Policy was released in June 2003 and applies to all newly constructed ESDS Web pages.

ESDS is committed to following agreed best standards and good practice in Web design and usability. The underlying code of the ESDS Web site achieves compliance with W3C guidelines for XHTML and Cascading Style Sheets. It strives to meet Web Content Accessibility Guidelines and be Special Educational Needs Disability Act (SENDA) compliant. Where this is not feasible or practical, e.g., proprietary software programs such as Nesstar Light, we will provide an alternative method for users to obtain the assistance they need from our user support staff. JISC and UKOLN recommendations have been reviewed for this policy.

| Standards | Validation and Auditing Tools |

|---|---|

| XHTML 1.0 Transitional http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/ |

W3C XHTML validation service http://validator.w3.org/ |

| CSS Level 2 http://www.w3.org/TR/REC-CSS2/ | W3C's CSS validation service http://jigsaw.w3.org/css-validator/ |

| WCAG 1.0 Conformance Level: all Priority 1 checkpoints, most Priority 2 checkpoints, and some Priority 3 checkpoints. |

A-prompt http://aprompt.snow.utoronto.ca/ Bobby http://bobby.watchfire.com/bobby/ |

For more detailed information about accessibility standards and how best to implement them see:

HTML is the recommended format for small documents and Web pages.

ESDS also provides access to significant amounts of lengthy documentation to users as part of its service. For these lengthier, more complex documents, we generally follow these JISC recommendations.

If a link leads to a non-HTML file, e.g., a zip or Adobe PDF file, this will be clearly indicated.

Portable Document Format (PDF)

For documents provided in PDF, a link to the Adobe free viewer will be made available.

Rich Text Format (RTF)

All leading word processing software packages include a standard facility for

reading RTF and some documents may therefore be made available in this format.

The ESDS is committed to keeping the links on its pages as accurate as possible.

ESDS Web pages are checked using Xenu Link Sleuth [4] or an equivalent checker, on a monthly basis.

ESDS catalogue records are checked using Xenu Link Sleuth or an equivalent checker on a monthly basis.

ESDS Web page links are manually checked every six months to verify that the content of the pages to which they link is still appropriate.

New templates and all pages are checked for use with these standard browsers:

We test our pages on PCs using Microsoft Windows operating systems. We do not have the equipment to test on an Apple Macintosh platform and rely on the standards we use to assure accessibility.

Diane Geraci and Sharon Jack

Economic and Social Data Service

UK Data Archive

University of Essex

Wivenhoe Park

Colchester

Essex

UK

CO4 3SQ

For QA Focus use.

It is important that HTML resources comply with the HTML standard. Unfortunately in many instances this is not the case, due to limitations of HTML authoring and conversion tools, a lack of awareness of the importance of HTML compliance and the attempts made by Web browsers to render non-compliant resources. This often results in large numbers of HTML pages on Web sites not complying with HTML standards. An awareness of the situation may be obtained only when HTML validation tools are run across the Web site.

If large numbers of HTML pages are found to be non-compliant, it can be difficult to know what to do to address this problem, given the potentially significant resources implications this may involve.

One possible solution could be to run a tool such as Tidy [1] which will seek to automatically repair non-compliant pages. However, in certain circumstances an automated repair could results in significant changes to the look-and-feel of the resource. Also use of Tidy may not be appropriate if server-side technologies are used, as opposed to simple serving of HTML files.

This case study describes an alternative approach, based on use of W3C's Web Log Validator Tool.

W3C's Log Validator Tool [2] processes a Web site's server log file. The entries are validated and the most popular pages which do not comply with the HTML standard are listed.

The Web Log Validator Tool has been installed on the UKOLN Web site. The tool has been configured to process resources on the QA Focus area (i.e. resources within the http://www.ukoln.ac.uk/qa-focus/ area.

The tool has been configured to run automatically once a month and the findings held on the QA Focus Web site [3]. An example of the output is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Output From The Web Log Validator Tool

When the tool is run an email is sent to the Web site editor and the findings are examined. We have a policy that we will seek to fix HTML errors which are reported by this tool.

This approach is a pragmatic one. It helps us to prioritise the resources to fix by listed the most popular pages which are non-compliant. Since only 10 non-compliant pages are listed it should be a relatively simple process to fix these resources. In addition if the errors reflect errors in the underlying template, we will be in a position to make changes to the template, in order to ensure that new pages are not created containing the same problems.

We have internal procedures for checking that HTML pages are compliant. However as these procedures are either dependent on manual use (checking pages after creation or updating) or run periodically (periodic checks across the Web site) it is useful to make use of this automated approach as an additional tool.

Ideally this tool would be deployed from the launch of the Web site, in order to ensure best practices were implemented from the start.

Brian Kelly

UKOLN

University of Bath

BATH

UK

BA2 7AY

Email: B.Kelly AT ukoln.ac.uk

For QA Focus use.

Exploit Interactive [1] was a pan-European Web magazine, which was funded by the European Commission's Telematics for Libraries programme. The magazine was one of the project deliverable of the EXPLOIT project, which aimed to promote the results of EU library projects and to facilitate their take-up by the market of library and information systems. The magazine ran for seven issues between May 1999 and October 2000. During its lifetime the magazine developed and maintained a strong and involved community of Exploit Interactive readers, authors, project partners and information providers and provided a forum for discussion within the EU Telematics for Libraries community.

Prior to the the last issue being published it was recognised that maintaining the site could possibly be a problem. Funding would cease and there would no longer be a member of staff working on the site.

Note that this case study does not address the wider long-term preservation issues. In particular it does not address:

The case study provides a pragmatic approach to access to the Web site after the project funding has finished.

It was decided to agree on a short-medium term access strategy for the Exploit Interactive Web site. This strategy would list policies and procedures for maintenance of the site for the next 10 years. It would also allow us to allocate money to certain activities.

10 years was decided upon primarily because the preservation industry rule of thumb is that data should be migrated every 10 years. It is unlikely that we will have the resources to migrate the Exploit Interactive Web site.

We will use the following procedures:

The area on which Exploit Interactive is held was measured:

Disk Size: 3.92 Gb (3920 Mb)

Exploit Interactive live site: 62.9 Mb

Exploit Interactive development site: 70.3 Mb

Exploit Interactive log files: 292 Mb

Exploit Interactive currently takes up 425.4 Mb of disk space.

The cost of this space is negligible bearing in mind you can purchase 30 Gb disk drives for about £40.

We have established that the domain name has been paid for until 23rd October 2008. We feel this is a sufficiently long period of time.

Two years on from the end of funding there have been very few problems adhering to the access strategy. The domain name has been held and a regular link checking audit has been initiated [2] Time spent on the maintenance of the site, such as link checking, has been minimal (about 30 minutes per year to run a link check and provide links to the results).

There are a number of potential problems which we could face:

However in practice we think such possibilities are unlikely.

We are confident that we will be able to continue to host this resource for at least 3 years and for a period of up to 10 years. However this is, of course, dependent on our organisation continuing to exist during this period.

Brian Kelly

UKOLN

University of Bath

BATH

UK

Tel: +44 1225 385105

For QA Focus use.

The UK Centre for Materials Education [1] supports academic practice and innovative learning and teaching approaches in Materials Science and Engineering, with the aim of enhancing the learning experience of students. The Centre is based at the University of Liverpool, and is one of 24 Subject Centres of the national Learning and Teaching Support Network [2].

Within any field, the use of discipline-specific language is widespread, and UK Higher Education is no exception. In particular, abbreviations are often used to name projects, programmes or funding streams. Whilst use of these initialisms can be an essential tool of discussion amongst peers, they can also reduce accessibility and act as a barrier to participation by others.

In this context, many individuals and organisations maintain glossaries of abbreviations. However, glossaries of this nature usually require manual editing which can be incredibly resource intensive.

This case study describes a tool developed at the UK Centre for Materials Education to help demystify abbreviations used in the worlds of Higher Education, Materials Science, and Computing, through the use of an automated 'Web crawler'.

The HTML 4 specification [3] provides two elements that Web authors can use to define abbreviations mentioned on their Web sites; <abbr> to markup abbreviations and <acronym> to markup pronounceable abbreviations, known as acronyms.

The acronyms and abbreviations are normally identified by underlining of the text. Moving the mouse over the underlined words in a modern browser which provides the necessary support (e.g. Opera and Mozilla) results in the expansion of the acronyms and abbreviations being displayed in a pop-up window. An example is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Rendering Of The <ACRONYM> Element

Using this semantic markup as a rudimentary data source, the crawler retrieves Web pages and evaluates their HTML source code for instances of these tags. When either of the tags is found on a page, the initials and the definition provided are recorded in a database, along with the date/time and the URL of the page where they were seen.

The pairs of abbreviations and definitions identified by the crawler are then made freely available online at [4] as illustrated in Figure 2 to allow others to benefit from the work of the crawler.

The limiting factor first encountered in developing the crawler has been the lack of Web sites making use of the <abbr> and <acronym> tags. Consequently, the number of entries defined in the index is relatively small, and the subject coverage limited. Sites implementing the tags are predominantly those that address Web standards and accessibility, leading to a strong bias in the index towards abbreviations used in these areas.

A number of factors likely contribute to a lack of use of the tags. Firstly, many Web authors might not be aware of the existence of the tags. Even in the current generation of Web browsers, there is little or no support for rendering text differently where it has been marked up as an abbreviation or acronym within a Web page. Therefore there is little opportunity to discover the tags and their usage by chance.

The second major factor affecting the quality of the index produced by the crawler has been the inconsistent and occasionally incorrect definition of terms in pages that do use the tags. Some confusion also exists about the semantically correct way of using the tags, especially the distinction between abbreviations and acronyms, and whether incorrect semantics should be used in order to make use of the browser support that does exist.

Figure 2: The Glossary Produced By Harvesting <ABBR> and <ACRONYM> Elements

To provide a truly useful resource, the crawler needs to be developed to provide a larger index, with some degree of subject classification. How this classification might be automated raises interesting additional questions.

Crucially, the index size can only be increased by wider use of the tags. Across the HE sector as a whole, one approach might be to encourage all projects or agencies to 'take ownership' of their abbreviations or acronyms by defining them on their own sites. At present this is rarely the case.

In order to provide a useful service the crawler is reliant on more widespread deployment of <acronym> and <abbr> elements and that these elements are used correctly and consistently. It is pleasing that QA Focus is encouraging greater usage of these elements and is also addressing the quality issues [4].

Lastly, if sites were to produce their pages in XHTML [5] automated harvesting of information in this way should be substantially easier. XML parsing tools could be used to process the information, rather than relying on processing of text strings using regular expressions, as is currently the case.

Tom Heath

Web Developer

UK Centre for Materials Education

Materials Science and Engineering

Ashton Building, University of Liverpool

Liverpool, L69 3GH

Email t.heath@liv.ac.uk

URL: <http://www.materials.ac.uk/about/tom.asp>

After hearing about the automated tool which harvested <abbr> and <acronym> elements [1] it was decided to begin the deployment of these elements on the QA Focus Web site. This case study reviews the issues which needed to be addressed.

The <abbr> and <acronym> elements were developed primarily to enhance the accessibility of Web pages, by allowing the definitions of abbreviations and acronyms to be displayed. The acronyms and abbreviations are normally identified by underlining of the text. Moving the mouse over the underlined words in a modern browser which provides the necessary support (e.g. Opera and Mozilla) results in the expansion of the acronyms and abbreviations being displayed in a pop-up window. An example is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Rendering Of The <ACRONYM> Element

As Tom Heath's case study describes, these elements can be repurposed in order to produce an automated glossary.

Since the QA Focus Web site contains many abbreviations and acronyms (e.g. Web terms such as HTML and SMIL, programme, project and service terms such as JISC, FAIR and X4L and expressions from the educational sector such as HE and HEFCE it was recognised that there is a need for such terms to be explained. This is normally done within the text itself e.g. "The JISC (Joint Information Systems Committee) ...". However the QA Focus team quickly recognised the potential of the <abbr> and <acronym> harvesting tool to produce an automated glossary of tools.

This case study describes the issues which QA Focus needs to address in order to exploit the harvesting tool effectively.

The QA Focus Web site makes use of PHP which assemble XHTML fragments. The HTML-Kit authoring tool is used to manage the XHTML fragments. This approach was used to create <abbr> and <acronym> elements as needed e.g.:

<abbr title="Hypertext Markup Language">HTML</abbr>

In order to ensure that the elements had been used correctly we ensure that pages are validated after they have been updated.

The harvesting tool processed pages on the UKOLN Web site, which included the QA Focus area. When we examined the automated glossary which had been produced [2] we noticed there were a number of errors in the definitions of abbreviations and acronyms, which were due to errors in the definition of terms on the QA Focus Web site.

Although these errors were quickly fixed, we recognised that such errors were likely to reoccur. We recognised the need to implement systematic quality assurance procedures, especially since such errors would not only give incorrect information to end users viewing the definitions, but also any automated glossary created for the Web site would be incorrect.

In addition, when we read the definitions of the <abbr> and <acronym> elements we realised that there were differences between W3C's definitions of these terms and Oxford English Dictionaries of these terms in English usage.

We also recognised that, even allowing for cultural variations, some terms could be classed either as acronyms or abbreviations. For example the term "FAQ" can either be classed as an acronym and pronounced "fack" or an abbreviation with the individual letters pronounced - "eff-ay-queue".

A summary of these ambiguities is available [3].

We recognised that the <abbr> and <acronym> elements could be used in a number of ways. A formally dictionary definition could be used or an informal explanation could be provided, possible giving some cultural context. For example the name of the FAILTE project could be formally defined as standing for " Facilitating Access to Information on Learning Technology for Engineers". Alternatively we could say that "Facilitating Access to Information on Learning Technology for Engineers. FAILTE is the gaelic word for 'Welcome', and is pronounced something like 'fawl-sha'.".

We realised that there may be common variations for certain abbreviations (e.g. US and USA). Indeed with such terms (and others such as UK) there is an argument that the meaning of such terms is widely known and so there is no need to explicitly define them. However this then raises the issue of agreeing on terms which do not need to be defined.

We also realised that there will be cases in which words which would appear to be acronyms or abbreviations may not in fact be. For example UKOLN, which at one stage stood for 'UK Office For Library And Information Networking' is now no longer an acronym. An increasing number of organisations appear to be no longer expanding their acronym or abbreviation, often as a result of it no longer giving a true reflection of their activities.

Finally we realised that we need to define how the <abbr> and <acronym> elements should be used if the terms are used in a plural form or contain punctuation e.g.: in the sentence:

JISC's view of ...

do we use:

<acronym title="Joint Information Systems Committee">JISC's<acronym> or

<acronym title="Joint Information Systems Committee">JISC<acronym>'s ...

We recognised that we need to develop a policy on our definition or acronyms or abbreviations and QA procedures for ensuring the quality.

The policies we have developed are:

We will seek to make use of the <acronym> and <abbr> elements on the QA Focus Web site in order to provide an explanation of acronyms and abbreviations used on the Web site and to have the potential for this structured information to be re-purposed for the creation of an automated glossary for the Web site.

We will use the Oxford English Dictionary's definition of the terms acronyms and abbreviations. We treat acronyms as abbreviations which are normally pronounced in standard UK English usage as words (e.g. radar, JISC, etc.); with abbreviations the individual letters are normally pronounced (e.g. HTML, HE, etc.). In cases of uncertainty the project manager will adjudicate.

The elements will be used with the formal name of the acronyms and abbreviations and will not include any punctuation.

We will give a formal definition. Any additional information should be defined in the normal text.

We will not define acronyms or abbreviations if they are no longer to be treated as acronyms or abbreviations.

Implementing QA procedures is more difficult. Ideally acronyms and abbreviations would be defined once within a Content Management System and implemented from that single source. However as we do not have a CMS, this is not possible.

One aspect of QA is staff development. We will ensure that authors of resources on the QA Web site are aware of how these elements may be repurposed, and thus the importance of using correct definitions.

We will liaise with Tom Heath, developer of the acronym and abbreviation harvester to explore the possibilities of this tool being used to display usage of <abbr> and <acronym> elements on the QA Focus Web site.

Although the issues explored in this case study are not necessarily significant ones the general issue being addressed is quality of metadata. This is an important issue, as in many cases, metadata will provide the 'glue' for interoperable services. We hope that the approaches described in this case study will inform the work in developing QA procedures for other types of metadata.

QA Focus Comments

For QA Focus use.

Citation Details

Creating Accessible Learning And Teaching Resources: The e-MapScholar Experience, Kent, D. and Robertson, L., QA Focus case study 04, UKOLN,

<http://www.ukoln.ac.uk/qa-focus/documents/case-studies/case-study-04/>

First published November 2002.

Changes